|

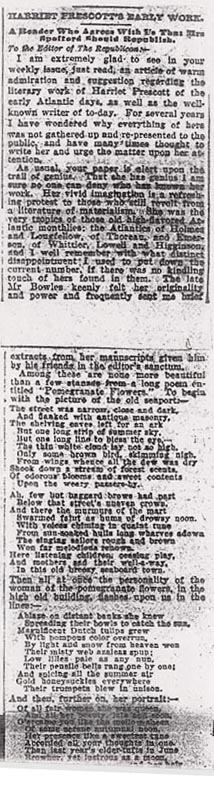

HARRIET PRESCOTT'S EARLY WORK.

A Reader Who Agrees With Us That Mrs Spofford Should Republish.

To the Editor of the Republican: -

I am extremely glad to see in your weekly issue, just read, an article of warm admiration

and suggestion regarding the literary work of Harriet Prescott of the early Atlantic days, as well

as

the well-known writer of to-day. For several years I have wondered why everything of hers was

not gathered up and re-presented to the public, and have many times thought of write her and

urge

the matter upon her attention.

As usual, your paper is alert upon the trail of genius. That she has genius I am sure no one

can deny who has known her work. Her vivid imagination is a refreshing protest to those who

still

revolt from a literature of materialism. She was the very tropics of those old high-flavored

Atlantic

monthlies: the Atlantics of Holmes and Longfellow, of Thoreau, and Emerson, of Whittier,

Lowell

and Higginson, and I well remember with what distinct disappointment I used to put down the

current number, if there was no kindling touch of hers found in them. The late Mr. Bowles keenly

felt her originality and power and frequently sent me brief extracts from her manuscripts given him

by his friends in the editor's sanctum.

Among these are none more beautiful than a few stanzas from a long poem entitled

"Pomegranate Flowers." To begin with the picture of the old seaport:--

The street was narrow, close and dark,

And flanked with antique masonry,

The shelving eaves left for an ark

But one long strip of summer sky,

But one long line to bless the eye,--

The thin white cloud lay not so high

Only some brown bird, skimming nigh,

From wings whence all the dew was dry

Shook down a stream of forest scents,

Of odorous blooms and sweet contents

Upon the weary passers-by.

Ah, few but haggard brows had part

Below that street's uneven crown,

And there the murmurs of the mart

Swarmed faint as hums of drowsy noon.

With voices chiming in quant tune

From sun-soaked hulls long wharves adown

The singing sailors rough and brown

Won far melodious renown.

Here listening children, ceasing play,

And mothers sad their well-a-way,

In this breezy seaboard town.

Then all at once the personality of the woman of the pomegranate flowers, in the high old

building,

flashes upon us in the lines:--

Ablaze on distant banks she knew

Spreading their bowls to catch the sun,

Magnificent Dutch tulips grew

With pompous color overrun,

By light and snow from heaven won

Their misty web azaleas spun:

Low lilies pale as any nun,

Their pensile bells rang one by one:

And spicing all the summer air

Gold honeysuckles everywhere

Their trumpets blew in unison.

And then, further on, her portrait:--

Of all fair women she was queen,

And all her beauty, late and soon,

O'ercame you like the mellow sheen

Of some serene autumnal noon.

Her presence like a sweetest tune

Accorded all your thoughts in one.

Than last year's elder-tufts in June

Browner, yet lustrous as a moon.

|

S.H.D. Commonplace Book (16:35:1),

Martha Dickinson Bianchi Collection,

John Hay Library, Brown University Libraries

|

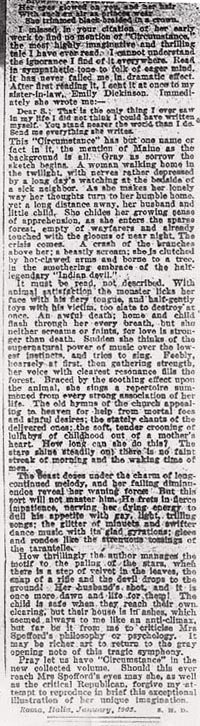

Her eyes glowed on you, and her hair

With such an air as princes wear

She trimmed black-braided in a crown.

I missed in your citation of her early work to find no mention of "Circumstance," the most

highly imaginative and thrilling tale I have ever read. I cannot understand the ignorance I find of

it

everywhere. Read in sympathetic tone to folk of older eager mind, it has never failed me in

dramatic effect. After first reading it, I sent it at once to my sister-in-law, Emily Dickinson.

Immediately she wrote me:--

Dear S.: That is the only thing I ever saw in my life I did not think I could have

written myself. You stand nearer the world than I do. Send me everything she writes.

This "Circumstance" has but one name or fact in it, the mention of Maine as the background is all.

Gray as sorrow the sketch begins. A woman walking home in the twilight, with nerves rather

depressed by a long day's watching at the bedside of a sick neighbor. As she makes her lonely

way

her thoughts turn to her humble home, yet a long distance away, her husband and little child. She

chides her growing sense of apprehension, as she enters the sparse forest, empty of wayfarers and

already touched with the glooms of near night. The crisis comes. A crash of the branches above

her; a beastly scream; she is clutched by hot-clawed arms and borne to a tree, in the smothering

embrace of the half-legendary "Indian devil."

It must be read, not described. With animal satisfaction the monster licks her face with his

fiery tongue, and half-gently toys with his victim, too elate to destroy at once. An awful death;

home and child flash through her every breath, but she neither screams nor faints, for love is

stronger than death [echoing ED]. Sudden she thinks of the supernatural power of music over the

lowest instincts, and tries to sing. Feebly, hoarsely at first, then gathering strength, her voice with

clearest resonance fills the forest. Braced by the soothing effect upon the animal, she sings a

repertoire summoned from every strong association of her life. The old hymns of the church

appealing to heaven for help from mortal foes and sinful desires; the stately chants of the delivered

ones; the soft, tender crooning of lullabys of childhood out of a mother's heart. How long can she

do this? The stars shine steadily on; there is no faint streak of morning and the waking time of

men.

The beast dozes under the charm of long-continued melody, and her failing diminuendos

reveal her waning force. But this sort will not master him. He frets in fierce impatience, nerving

her dying energy to dull his appetite with gay, light, trilling songs; the glitter of minuets and

swifter

dance music with its glad gyrations; glees and rondos like the strenuous tossings of the tarantelle.

How thrillingly the author manages the motif to the paling of the stars, when there is a step

of velvet in the leaves, the snap of a rifle and the devil drops to the ground! Her husband's shot,

and it is once more dawn and life for them! The child is safe when they reach their own clearing,

but their house is in ashes, which seemed always to me like an anti-climax, but far be it from me to

criticise Mrs Spofford's philosophy or psychology. It may be richer art to return to the gray

opening note of this tragic symphony.

Pray let us have "Circumstance" in the new collected volume. Should this ever reach Mrs

Spofford's eyes may she, as well as the critical Republican, forgive my attempt to reproduce in

brief this exceptional illustration of her unique imagination.

Rome, Italia, January, 1903. S.H.D.

|